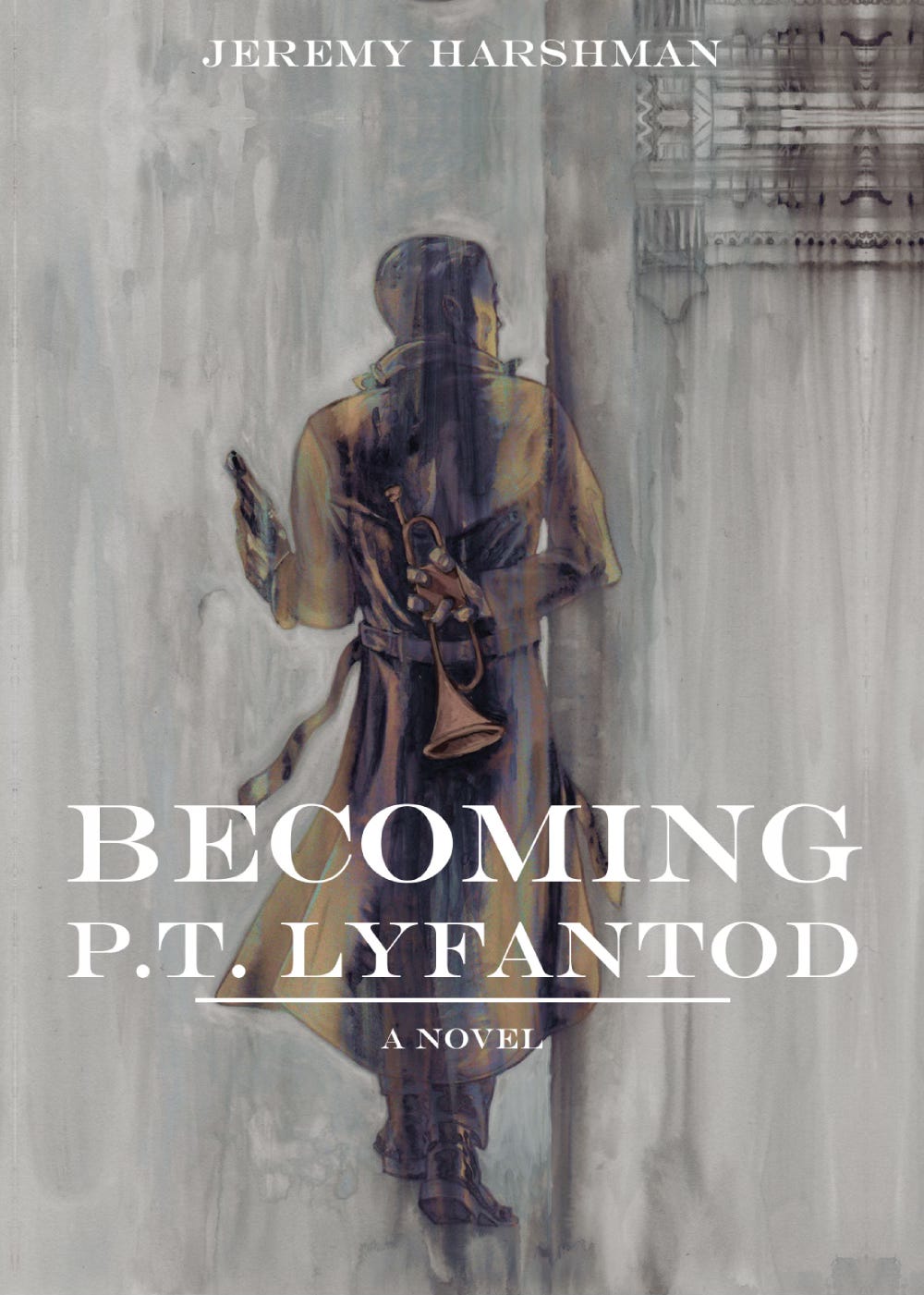

What follows is Part 13 of Becoming P.T. Lyfantod

If you missed Part 1, start there:

I spent the first half of the trip peering over my shoulder to make sure no one was following. Eventually I managed to convince myself that I really was pushing this newfound paranoia a bit too far and gave off.

Mostly.

Sketty Library was in a little old red-brick building smaller than most of the flats and townhouses surrounding it. It looked more like a country cottage than a repository of earthly knowledge. There was a much larger, more impressive library downtown, but since I didn’t have my bike, and this one was a short walk from the park, it would have to do. I found a table near the back in the darkest corner I could find, which was not very dark at all, the library being unfortunately well lit.

It wasn’t crowded but it wasn’t empty either. There were a few families gathered in the kids’ section, the parents feigning interest in picture books and pop-ups, and probably most of the kids as well. I reckoned they were safe enough. I couldn’t imagine faerie children being involved in…whatever this was. The rest of the library was scattered with senior citizens and several people presumably doing the sort of thing I was only pretending to.

I sat with my back to the wall, facing the entrance as Eremin would. Then, using my rucksack as a shield, I withdrew the book from my jacket. I scanned the room. The tables nearby were empty, and no one seemed to be paying me any attention. I borrowed a wilderness survival magazine from a nearby rack and wrapped it around the book. Nobody would know what I was reading, even if they looked. Once the book was safely nestled in an article about starting fire with twine and the second knuckle of your ring finger, I opened it back to the page marked with the ribbon.

I studied the text abstractly, as a forest rather than individual trees. The paper was so thin I could see the words showing through from the other side. I was amazed they’d been able to stuff so much information into so small a space. The bottoms of both pages were crammed with footnotes, directing me to this page or that, to other essays, entries in the glossary, or the appendices. And hidden among it all was a clue that would tell me what I needed to know. I had no idea what it would look like, but I supposed I’d know it when I saw it. I dove in.

This was the first time I’d ever done anything resembling research, and I discovered, to my surprise, that I…didn’t hate it. It felt like detective work. I sought to understand, in this sea of information, what was relevant and what was simply noise. It took me all of five minutes to realize I’d probably want to take notes and mark pages. I’d far too much reverence for books to consider folding corners. I tore out strips of lined notebook paper and began stuffing them between pages.

I had a hard time keeping on track or finishing any articles after the first two. I read a paragraph here, a paragraph there, flipping back and forth, looking up words I didn’t know, writing down names, dates, places, with half of the fingers on my left hand wedged between different pages for easy access. Gradually, I started piecing things together about the Tuatha Dé and their history. I read for hours. I began to understand who Willoughby meant when he mentioned the Milesians, the Nemedians, the Fir Bolg. I started recognizing all the different names for the Tuatha Dé: the Aos sí, the children of Danu, the Sidhe, the Good Folk… And I noticed other interesting things as well, like the similarities between the Irish Tír na nÓg and the Welsh Annwn—both words for some kind of otherworld, separate from but connected to our own. I wondered if they were the same place. I read about Cùchulainn. About Arawn. About Balor and the Fomorians. About druids and stone circles.

I felt I’d stumbled upon a whole new, magical world. I’d read plenty of fantasy up till then. Only a little over year ago, the four of us had decided to read The Lord of the Rings for the first time. That was when Meredith had become Merry. I remembered reading about barrow wights and not quite understanding. I hadn’t considered that those very barrows might be scattered across the British Isles.

Sometimes something would catch my eye, entirely unrelated to my search but absorbing nonetheless. Willoughby believed a small museum in Truro was concealing the bones of the giant Yspaddaden and demanded they show them to him. In the Book—by this point, it’d gotten capitalized in my head—he’d printed the entirety of their correspondence, increasingly antagonistic, in which the museum’s curator was called a number of shocking names. I was puzzling over Truro’s location—fascinated by the possibility of giants, wondering whether I could find these bones for myself—when I spied movement from the corner of my eye.

It turned out to be a woman looking at books on animals. But in glancing up, I also happened to notice the clock on the wall above her. It was 7:03.

“Oh no…”

I shoved the Book into my bag and scrambled from my chair. The porch light was on when I arrived home, panting, some fifteen minutes later. I opened the front door as slowly and quietly as I could. Inch by inch—

“You’re late.”

I winced. Mam-gu was in her easy chair, watching a cooking show with the sound way down. A man in a floppy white hat was dicing onions. She couldn’t possibly have seen me.

“Sorry.”

Mam-gu’s head turned. “I suppose you got caught up doing research?”

“Yeah, actually! I’ve been reading for hours.”

“Weren’t you supposed to be writing something?”

“I was, ah, getting to that.”

“Ahum.” She slid first one arm then the other back along the armrests of her chair and leaned forward in order to lever herself out. Once standing, she reached for the remote. The image on the telly squeezed itself into a horizontal line and winked out.

“Well, come on.” She made for the kitchen, the slightest hint of shuffle in her step. “Ham will put up with microwaving.” She hadn’t eaten either. I felt a pang of guilt. Mam-gu carried a plate of sliced ham from the table over to the microwave on the counter. There was a bowl of green beans and boiled potatoes, and a simple salad as well.

The beans and potatoes were mushy, as boiled vegetables tended to be. The salad had sliced radishes, which I liked. While I slathered my ham with mustard, I asked mam-gu how her day had been. She was still considering whether to be cross with me. She gave me a look and took her time in answering, helping herself to a portion of beans after I had done.

“Oh, it was fine,” she sighed eventually, shaking salt and pepper onto a lump of cold potato. “I cleaned the downstairs toilet and washed the linens. Not the best weather for drying in, but we must make do with what we’re given. I did a bit of gardening.” She forked a limp bean and held it up at me.

“They’re very good.”

She nodded. “I had a chat with Mrs. Evans down the street. Her granddaughter, Mary, is studying chemistry at King’s College in London. She’s going to be a scientist. It takes a lot of hard work to become a scientist. But they can really make a difference in the world. Take Sir David Brunt. Fine Welshman from Montgomeryshire. He’s considered the father of modern meteorology. Without him, we wouldn’t have—”

“Weather reports, I know.”

“That’s right. And a good thing too. Can you imagine? Every day, heading out the door, no idea what you’re in for? There might be a tornado going on outside, and you wouldn’t know until you looked! Thanks to Mr. Brunt and the scientific method, all you’ve got to do is turn on the telly and you’ll know right then whether it’s hot and sunny or if you’ll need a raincoat.”

“That’s true, I guess. Although…you could just look out the window.”

“And suppose you haven’t got windows?”

“Well, you could open the door without going through it—”

“And have a cyclone in your living room before you knew what happened.”

“It hasn’t happened yet.” I paused. “It might be interesting to have a cyclone in the living room.”

She nodded, slicing off a piece of ham and placing it in her mouth. “I’m pleased to hear you’re being so diligent in your studies. Spending an entire day on a project is quite unlike you.”

I smiled through a mouthful of potato. “It’s a subject I’m…very passionate about. You know…” She fixed me with an inquiring look. “Ah…history.”

“Oh. I’m quite fond of history myself. What are you writing about?”

“You are?” I stuffed my mouth with ham in a bid for time. Chewing enthusiastically, I nodded. “Itch about—mm—the—the…ancient peopleth of Great Britain!”

“The ancient peoples, you say.”

“That’s right. Did you know they buried people in great mounds? With treasure and all sorts of interesting artifacts. And they’ve been digging…excavating them. And finding out all kinds of interesting things. They’re called barrows. Or tumuli. That’s the plural of tumulus, you know. It’s Latin.”

Mam-gu regarded me in silence. I assumed what I imagined was a scholastic air.

“It seems you really have been reading,” she said at last, leaning back in her chair. I carefully swallowed my sigh of relief. “There’s applesauce in the fridge if you want it. After you finish your dinner.”

“Can I take it to go? I’ve really gotta finish this report.” I smiled and helped myself to more beans.