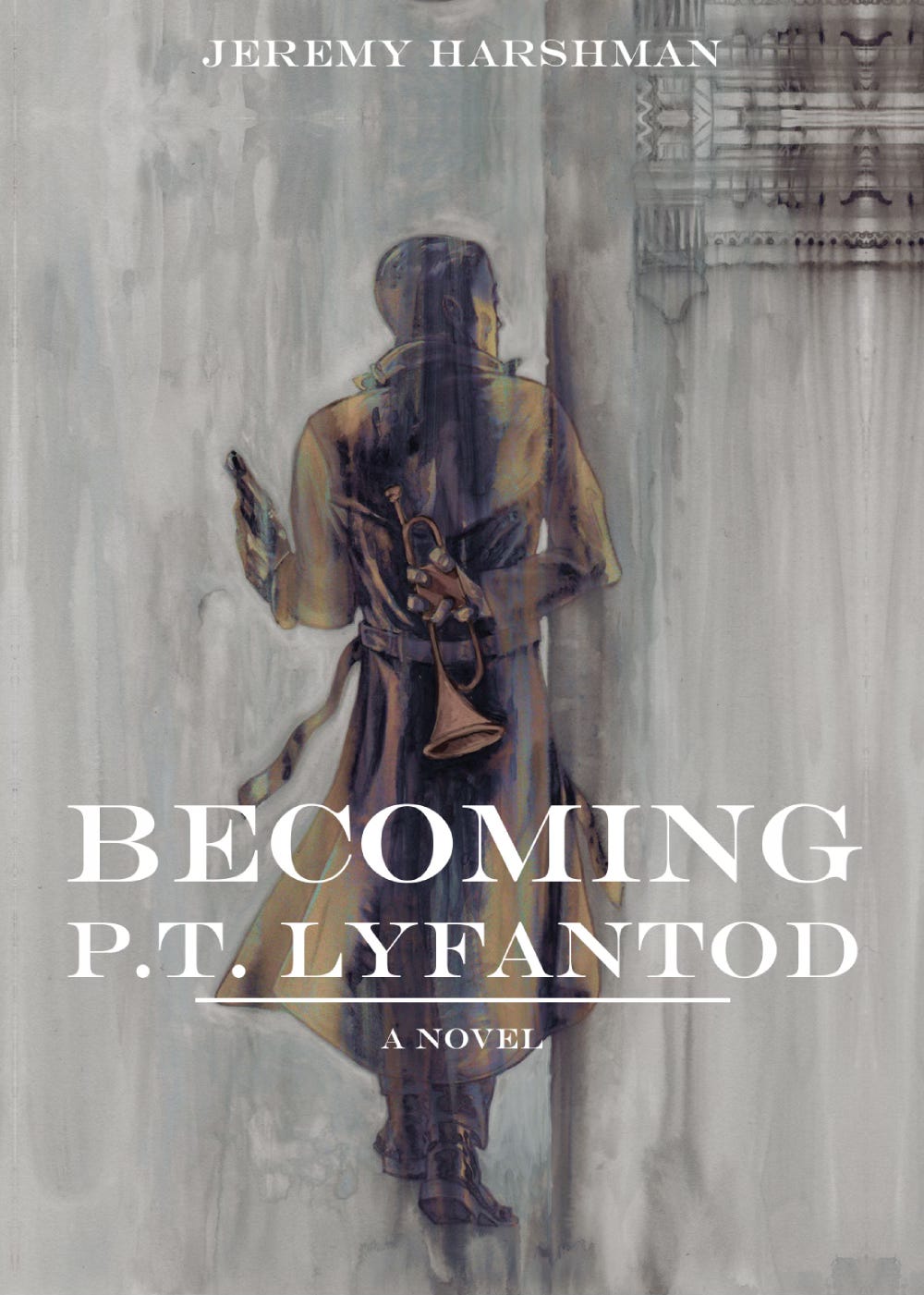

What follows is Part 23 of Becoming P.T. Lyfantod

If you missed Part 1, start there:

Chapter Seven:

Pais Dinogad

Branches thwacked my face and tugged at my clothes as I pushed through the bushes at Merry’s back. I hardly noticed.

“Tom?” she called.

“What’ve you found?” I shouted past her.

We found Tom by tripping over him. Merry fell first, and I came tumbling after. Behind me, Iain cried out, and before I knew it I was sandwiched.

“Get off!” Merry wheezed.

“I’m trying!”

“Stu!”

“I know!”

The weight on my back shifted. Someone’s elbow was in my cheek. The pressure grew, then the elbow disappeared. I climbed off Merry gingerly, painfully conscious of where I put my hands, then shuffled sideways into the wall of stabbing twigs. Beside me Iain stood red-faced and bent nearly double. Stuart had backed himself halfway into a bush, but he at least was upright. Merry righted herself grumbling, and we huddled over Tom, who made no attempt to rise because it would’ve been impossible.

“What the hell?” Merry growled.

Tom grinned up at her disarmingly, which made me want to kick him. I was somewhat consoled by the welt growing to one side of his forehead. “Now now. If you’re going to be cross, I might not share my discovery.”

“Cut the games, Tom,” Iain rumbled. Blood lined his cheek, and his jaw was twitching.

“Fine, fine.” Tom waved and scooted aside so we could see. Where his back had been, there was an expanse of moss-covered stone that thrust upward into the branches and leaves. And where the moss had been rubbed away…

Stuart gasped. “That’s writing!”

I gaped. “But you—! How did you…?”

Tom smirked back at me. “Told you I’d find it. Tom Firth always delivers.”

“If you’re suggesting this was anything other than an absolute fluke—” Iain said.

Tom was the picture of smug confidence. “The stone called to me. You lot are lucky I decided to share it with you at all. Except you, of course, Mer.” He winked. I wished he would stop doing that.

“Rubbish,” said Iain, “I saw you running away from those frogs.”

“Believe what you will. The fact is, I saw it first.”

“That d—”

“Enough!” Merry snapped. “What does it say?”

Tom shrugged. “No idea.”

“Move over.” Merry shoved Tom out of the way and began scraping at the age-old grime with surprising intensity. I dropped to my knees and started scraping myself. The stone was larger than I’d first realized. Taller than Iain, wider than Merry and I side by side. Most of it was hidden by the thick foliage overhead. We snapped off branches and threw them aside while Iain did his best to provide unobstructed light. The whole face of the stone appeared to be covered with writing, but none of it made any sense.

“Nyt anghei…” Merry read,“oll ny uei oradein.”

“What?” said Tom.

“It kind of sounds like Welsh,” said Stuart. “But I don’t understand any of it.”

“There’s more,” said Merry.

“A lot more.” I scratched at the moss with a broken twig. “It goes all the way up.”

“There’s some kind of design in the middle,” said Iain. “A circle.”

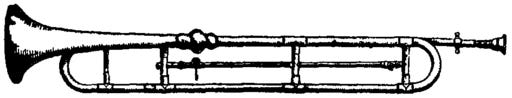

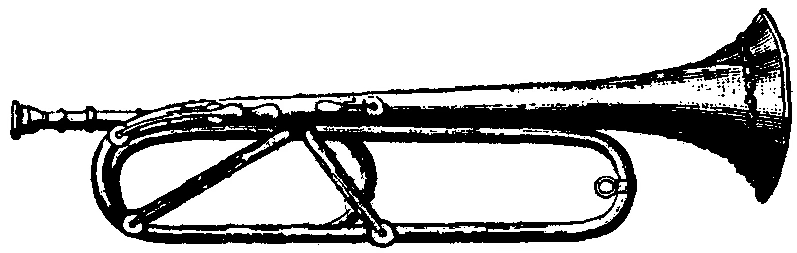

We worked frantically. My hands were filthy. Whatever doubts I’d had that this was Lightfoot’s stone vanished when Merry uncovered Iain’s circle: a twisting knot with a horn in the center. A musical instrument.

“This is it! We found it!”

“Technically—” began Tom.

“Shut up!” Iain, Stuart, and I shouted in unison.

“What does it say up there?” Merry craned her neck to see the top. My height was no advantage. The letters were legible, but the words were gibberish. I sounded it out as best I could. “Peis dinogat e vreith vreith, o grwyn—”

“Pais dinogad!” cried Stuart and Merry together. Everyone else jumped.

I goggled at them. “You know it?”

Merry glanced at Stuart, who nodded. “It’s a lullaby,” she said. “A very old one.”

“Seventh century, I think,” Stuart agreed.

“And the two of you know it because…” asked Iain.

“Because,” Merry said, “it’s famous.”

Stuart nodded. “It’s one of the oldest songs in Britain. And the reason it looks like Welsh but…not, is that it’s Brythonic, the linguistic ancestor of Modern Welsh.”

“Well, I’ve never heard of it,” said Tom, crossing his arms. As if that meant anything.

“My tad-cu used to sing it sometimes,” said Merry. “But not this version. I knew it looked familiar, but the words are so different.”

“We have to sing it,” I said, suddenly sure. “Merry, do you remember how it goes?”

“The melody, sure. I don’t know these words, but I don’t think it would be too hard…”

“Would you try?”

Looking uncharacteristically self-conscious, Merry nodded. It struck me how lucky it was that she was in choir. The rest of us played instruments but couldn’t sing. I’d seen Merry in plenty of school productions over the years. She was good, and that was good for us. She cleared her throat, squinting upwards in the light of Iain’s torch, and began to sing.

“Peis dinogat e vreith vreith. O grwyn balaot ban wreith. Chwit chwit chwidogeith…”

“Are you planning to speak the whole song?”

“I can’t very well sing it. You know I can’t.”

“Fine. What does it mean?”

“I didn’t know it then, but it’s a mother telling her son about his father’s skill at hunting. ‘At whatever your father aimed his spear, be it boar, or wild cat, or fox, none would escape but that with strong wings.’”

“Doesn’t sound like any magic I’ve ever heard.”

“I don’t believe it is. When Lightfoot put up that first stone, I think he wanted a song that most people might be expected to know. It was a test of singing ability. If you sang it well… Well, you’ll see. And Merry sang it beautifully.”

We listened breathlessly as Merry sang. The song did sound familiar, though where I might’ve heard it, I hadn’t a clue. An instant and an eternity later, she reached the end. The silence echoed in the absence of her voice. We waited. I watched the stone, hardly blinking. Merry mostly looked embarrassed.

Iain coughed. “Maybe it’s broken.”

Stuart’s eyes were on our dark surroundings. “What if you’ve called something? A ghost, or…”

“There’s no such thing as ghosts.” Merry shook her head. “I don’t know why I thought—”

The five of us gasped at once as a blue-green flame flickered to life in the bell of the graven horn. We watched in disbelief as it flowed smoothly outward along the lines of the knot. Over, under, around it went, until the whole circle was lit with glowing lines that pulsed gently in the dark.

“Bloody hell…” Iain breathed.

Tom waved his hand over the flame. “There’s no heat,” he said wonderingly. “I wonder what’ll happen if I—”

“Tom, wait!” Merry cried.

But it was too late.

Tom’s fingers brushed against the glowing scrollwork, and after his eyes went wide as saucers, he vanished. No one moved. We were stunned to silence. Unconsciously fingering the cross she wore around her neck, Merry looked at me. Her next move was written plainly in her eyes.

“Merry, no!” shouted Iain.

But her hand was already moving. A moment later, she winked out of existence as well.

“Move!” Iain shoved me into the bushes. It hurt. He slammed his open palm down onto the glowing knot, then he too was gone.

“Ow,” I muttered, extricating myself.

Stuart helped me up. “Are you alright?”

“Fine. Thanks.”

“Do you think we should…” He nervously eyed the knot. “Maybe we should wait for them to come out.”

“We don’t know if they are coming out, Stu. Or when.” I shook my head. “There’s no way I’m letting Tom Firth take this from me. Iain and Merry might need our help.”

Stuart swallowed but nodded. “Do you think it’ll be…another world?”

“I haven’t the faintest idea. Go together?”

“Yeah.”

Reaching out, I wondered if I was making the last, biggest mistake of my life. Rough stone brushed my fingertips, then the stone and everything else were gone.